Spying, sabotage, subversion, people-smuggling: the brave women who resisted the Nazis through non-violence

Many people think Nazi Germany was beaten only through military violence, and mainly by men. As Barack Obama said in 2009: “Nonviolence could not have halted Hitler’s armies”. In fact, non-violent action was widely used in resisting Nazism. Brave women often led it. They later got little recognition, though this is now changing.

Women in nations such as France, Germany and Holland gathered intelligence, founded resistance groups, published underground media and coordinated people-smuggling operations. Some engaged in sabotage. Their networking and people skills were invaluable, and their lack of visibility under a sexist regime was an asset. Some of these brave women sacrificed their lives for the cause.

It is useful to consider their impact today and how such female-led, non-violent movements might help people around the world resist dictatorships and invasions, such as in Ukraine.

Some German women used overt, concentrated tactics – such as those who were thrown into jail for speaking out against Hitler, and the “Rosenstrasse” group, who protested in Berlin in 1943. These non-Jewish women shouted for their Jewish husbands to be set free, despite the threat of being machine-gunned. Amazingly, they succeeded – at least in the short term – with about 2,000 men released. Most of these men survived the war.

Resistance campaigns ranged from those waged by individuals to those involving large sections of the population. For example, about 10,000 Norwegian teachers, supported by around 100,000 parents, successfully resisted the Nazification of schools. Dutch strikes in 1941 and 1943 involved hundreds of thousands.

But secret, dispersed tactics were more common.

Read more: Ukraine: nonviolent resistance is a brave and often effective response to aggression

Pioneer daredevils

Many women excelled at gathering and communicating intelligence. Frenchwoman Ruth “Malou” Altmann reported on German conversations overheard on trains, bistros and streets, and the messages she heard on secret radios, about matters such as troop movements. With her excellent German, her information was always exact and often very important. She memorised things such as the layout of a town hall so other resistance members could raid it for ration tickets. Travelling unnoticed by bike, with her three-year-old daughter, she avoided suspicion.

US citizen Virginia Hall had a fake leg and battled sexism to become the first Special Operations Executive (SOE) liaison officer of any gender. The SOE was a volunteer force set up to work with resistance groups in occupied societies and boost their morale.

Hall infiltrated Vichy command to get information on Nazi activities in France. She was a pioneer of spying, sabotage and subversion in an era when women were rarely thought heroic. Hers was a very modern form of resistance, based on propaganda and creating dissent within to topple a regime.

Underground media spread information to wide audiences to counter Nazi propaganda. German posters were torn down, and walls plastered with graffiti and stickers. Messages were typed on banknotes, which were scarce and rarely destroyed.

Flyers were written by Sophie Scholl’s White Rose group and posted around the country. Scholl was a kindergarten teacher, philosophy student and daughter of an ardent Nazi critic. She founded White Rose with her brother Hans and a group of like-minded friends in 1942.

She and Hans were arrested after dropping flyers into a courtyard at a Munich university. Convicted of high treason by the Nazis, she was executed in Munich on 22 February 1943, aged just 21.

Traute Lafrenz, the last surviving member of the White Rose, died last month, aged 103.

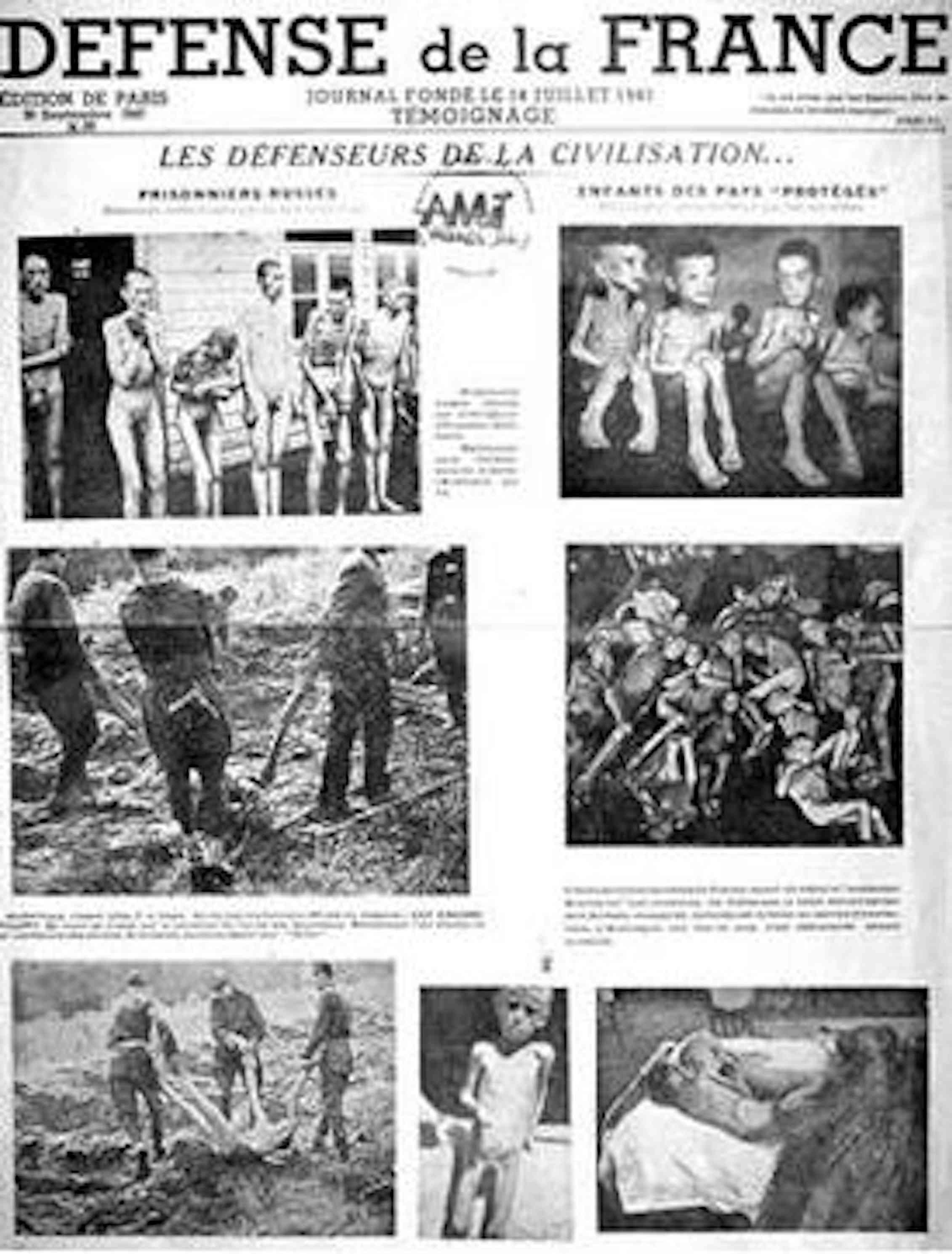

Charlotte Nadel was from a family of Russian immigrants to France. A librarian at the Sorbonne University, she became co-founder of the resistance group Défence de la France. Within two years, their publication grew from 5000 basic flyers to a newspaper with 150,000 copies. Although caught and imprisoned, Nadel was freed in August 1944 and kept resisting.

The Germans knew how important this underground media was. It corrected false stories, exposed the truth about roundups, recruited people into the Resistance, and encouraged them to act. Punishments for resisters included being sent to a concentration camp, or executed.

There were other dangers. Marie Servillat (alias “Lucienne”) had her arm crushed in a printing press for the underground newspaper Combat. In 1944 she was shot in the chest and legs and taken by the Gestapo to a hospital, but later escaped.

These newspapers gave the impression of a much larger movement. This was a clever tactic later used by the Otpor movement to end the Milosevic regime in Serbia.

Papers like Femmes Françaises asked mothers to protest for more food rations. On Bastille Day 1944, women were urged to place red, white and blue flowers on war monuments and march to the town halls demanding bread.

Agnès Humbert had studied at the Sorbonne and was a writer and historian at a Paris art museum. After the German invasion, with many men in prison camps, she became one of the first resistance leaders. She called one early flyer:

a glimmer of light in the darkness … Now we know for certain that we are not alone. There are other people who think like us, who are suffering and organising the struggle: soon a network will cover the whole of France, and our little group will be just one link in a mighty chain. We are absolutely overjoyed!

Underground media depicted the Nazi regime as lying, irrational, not natural, and vulnerable. It painted the Resistance as reasonable, sensible and rational.

Such media made resistance leaders think deeply, sort out their strategy, and speak clearly to the general public, who had to be persuaded before they would act.

Read more: A lockdown protester in Germany has caused a furore by comparing herself to an anti-Nazi hero

Hiding and smuggling people

Women led smuggling operations, hiding Jewish people and other evaders from the Holocaust. Individuals like young Dutchwoman Hannie Schaft hid people in their homes.

Groups like the National Movement Against Racism, led by Suzanne Spaak, a wealthy Belgian based in Paris, smuggled many children to remote villages.

Women also kept downed airmen, agents and escaped prisoners out of prison, helping them return to active service. At first impromptu, this aid soon turned into a complex set of escape lines involving about 10,000 helpers.

60-year-old Marie-Louise (code-named “Françoise”) Dissard took over one escape network. She found guides and safe houses. She bought food, civilian clothing and medical supplies. She opened her small flat as a headquarters. To get money, she went to Switzerland, climbing barbed-wire fences and dodging border guards.

Women, says historian Margaret Rossiter, “took a keen interest in helping [airmen] return to their bases, while many Frenchmen were involved in sabotage and guerrilla operations”. This shows how women and men worked differently in the Resistance, women mainly working in non-violent activities.

Some women, like Australian Nancy Wake, who was married to a rich French businessman, moved between non-violent and violent tactics. Wake began as an ambulance driver who fed prisoners of war. She then led escape lines, and was herself rescued from prison after beatings and questioning. After becoming an SOE agent, she went back to France to train and supply large resistance groups.

Sabotage

Resistance leader Agnès Humbert was arrested in 1941. Working as a slave in a German prison, she lifted her spirits by slowing the making of cloth and crates:

After every successful act of sabotage my heart feels lighter. It’s a sort of rite of atonement for me, between me and my conscience.

Polish-born Krystyna Skarbek, aka Christine Granville, served longer than any other of Britain’s wartime women agents and became famous for her bravery. Resourceful and effective, she gathered intelligence in Hungary, Poland and France. She also wrecked German communications, and destroyed barges carrying oil from Romania to Germany.

These women worried about violence and felt moral concerns. Said Wake,

I hate war and violence but, if they come, then I don’t see why we women should just wave our men a proud goodbye and then knit them balaclavas.

Teenaged resister Simone Segouin was from a French farming family near Chartres. At 14 she was helping her father shelter and feed resistance members. She became a courier, riding a repainted bike stolen from Germans, in the guise of a “sweet-faced farmer’s daughter carrying baguettes in a basket”. An expert in explosives and guerrilla tactics, she helped liberate Chartres and Paris in August 1944. Asked in 2014 if she had ever killed anyone, she answered that she may have, during an ambush.

You shouldn’t have to kill someone like that. It’s true, the Germans were our enemies, it was the war, but I don’t draw any pride from it.

She become a paediatric nurse, had six children, and died aged 97 in February this year.

Spying, though non-violent, often helped the Allies carry out violence. In 1940 Humbert worried about moving from propaganda activities to smuggling maps and military documents for the Allies:

I know all too well what they will do with it. Because of my meddling there will be widows, inconsolable mothers, fatherless children … French people, living peaceful lives – will be killed and wounded, children maimed. Where are my lofty humanitarian ideals now? Have I taken leave of my senses? … What a filthy business.

After the war she joined the Friends of Peace, arguing against war.

Some women were pacifists, such as SOE radio operator Noor Inayat Khan. She came from Indian Muslim royalty, and would be shot in Dachau concentration camp. She had struggled with the moral questions of war, as her brother Vilayat explained:

[We] had been brought up with the policy of Gandhi’s nonviolence, and at the outbreak of war we discussed what we would do. She said, ‘Well, I must do something, but I don’t want to kill anyone.’

Suzanne Spaak only used non-violent methods to smuggle people. Arrested by the Gestapo in October 1943 and condemned to death, she wrote: “I hold that human life is sacred.” She was very sorry for the death sentence of a fellow resister, which she felt was her fault. Once arrested, Spaak was kept in horrific conditions and subjected to torture. She was executed on 12 August, 1944, just days before the liberation of Paris.

Read more: Thinking back to Gandhi amongst brute force and umbrellas

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of smuggling and hiding people was most obvious, with 7,220 Jewish people saved in Denmark alone. In Holland, Truus Wijsmuller was a social worker. Unable to have children, she dedicated herself to helping the children of others instead. Politically involved, she had a large network of friends. She smuggled Jewish children into Holland, including a Polish boy hidden under her skirt.

After Kristallnacht, she realised that Jewish children were no longer safe on the continent. She negotiated with the Nazis to move about 10,000 Jewish children to England. When the war began, she continued this work illegally.

Nancy Wake’s escape line (one of many) smuggled 1,037 men from France. Many airmen later said they escaped only because of women’s help.

The effects of spying and underground media were more subtle, but helped grow groups such as the Maquis. These were mainly young, working-class men who had escaped into the forests and mountains to avoid being sent to Germany to work. They organised themselves into active resistance groups and were vital for the Allied advance after D-Day. Women also joined the Maquis and were very effective leaders.

For example, while an all-male Maquis group in the Vosges region spent most of the war in hiding, Krystyna Skarbek made the first contact between the French and Italian Resistance on opposite sides of the Alps before D-Day. She freed captured Resistance leaders and persuaded a whole German garrison on a strategic mountain pass to defect, without any bloodshed.

People skills

Women often began resistance movements, growing their numbers through networking and people skills, using their less visible positions within a sexist regime.

Virginia Hall was great at influencing and connecting people, winning over key French officials and getting far more information from them than her male peers. She made friends with Suzanne Bertillon, chief censor of the foreign press in Vichy’s Ministry of Information. Bertillon set up a network of 90 contacts, including farmers, mayors and businessmen, to give Hall information on industrial production, troop movements and a German submarine base being built in Marseille. The base was later destroyed by Allied bombs.

Spaak also showed excellent recruiting skills, bringing together women from all classes – social workers, clergy, girl scouts, officials and guards – including the Jewish communist immigrant Miriam Sokol. The women’s friendship rose above their political differences. In contrast, their husbands never got past their dislike for each other.

Women’s ability to quickly build broad networks of resistance challenges the common belief that armed men are better at dealing with ruthless opponents than unarmed women. These stories also show how women can step out of conventions and defy stereotypes.

It’s hard to point to one reason – either violent or not – for the defeat of Nazism. Each of the actions described, taken alone, eroded the Germans’ power in small ways. When put together they had a great impact. They provided useful intelligence for the Allied forces. They encouraged dissent, resistance and non-cooperation. They saved many lives. They got airmen back in the air. They wrecked Nazi resources.

Resistance came at a cost. Exact figures are hard to establish, but it’s thought that more than 4,000 women of various ages were hanged by Nazi forces (separate to those who died in the Holocaust). Many more were shot or guillotined. Although terrible, this is a tiny fraction of the 68 million or more killed by military violence during the war.

There were many failures of resistance at national and international levels. Some useful non-violent strategies were barely used, such as economic non-cooperation through boycotts, divestment and sanctions against the international companies which propped up Nazism.

Lessons today

Still, if ad hoc non-violent action had a role in defeating Nazism, it might succeed almost anywhere. It could possibly have worked last year in Ukraine, which has a history of successfully ending pro-Russian governments through nonviolent mass action. That’s much harder now the war is entrenched.

Non-violent action today could be improved and better resourced. Democracy movements in Ukraine, Myanmar, Syria and Sudan could be supported by much stronger global boycott and divestment systems and international peacemaking forces. Mass nonviolent resistance could begin with dispersed, stay-at-home strikes, which pose little risk. Experienced activists and trained volunteers could lead such resistance.

Military violence is expensive, consumes resources, has a huge carbon bootprint, and continues cycles of violence.

Non-violent action led by women is never easy. But it causes far fewer deaths and is more sustainable. Could it ultimately replace military violence?

Marty Branagan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.